Sayre Gomez’s paintings show LA ‘as it is, rather than a projection’

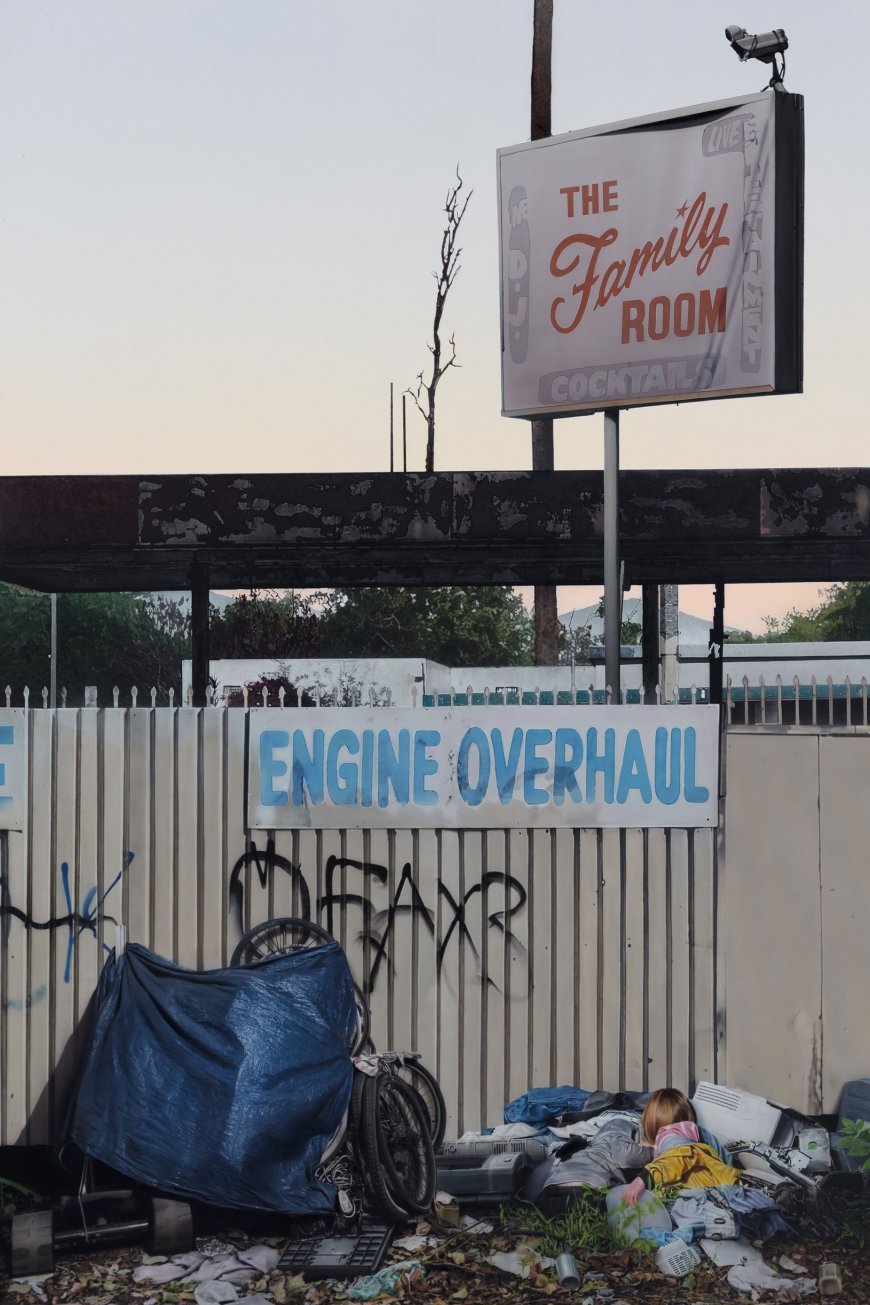

It was not until I looked at “Family Room” for the second time that I saw the two children. Underneath a faded sign advertising a “DJ,” “cocktails” and “live entertainment,” where a graffitied security fence gives way to piles of bike wheels, discarded clothes, broken bits of tech and some curtains, two small figures emerge, rummaging in the detritus.

The scene of decay and demise is a painting by LA-based artist Sayre Gomez, called “Family Room,” that brings together disparate elements of his hometown in an unnervingly photorealist style. The work forms part of his solo show “Heaven N’ Earth,” at art dealer Xavier Hufkens’ flagship gallery in Brussels, Belgium, exploring the complex dichotomies of the urban landscape.

“For the most part, I keep figures out of the paintings, so it was a tricky decision to include them,” Gomez said over Zoom of the image, which was inspired by a real family living in a make-shift encampment of tents and RVs across the road from his studio. “The kids (depicted) in that painting are my kids, but they became a surrogate for this situation.”

Gomez's work "Family Room," featuring two children rooting in the trash of an abandoned lot, was inspired by a real situation the artist encountered near his studio.

It’s a deeply disconcerting starting point to a show that stretches over four floors, juxtaposing Californian beaches, sunsets and glittering skylines with hulking construction machinery, abandoned cars and shopping carts set on fire. “Gomez devotes his attention to the physical and cultural survival techniques of those left behind in the wake of capitalist development,” reads the exhibition notes, “with a sincere commitment to documenting traces of lived experience in the ruins of deindustrialization.”

Or as Hufkens, who first showed Gomez’s work in Brussels in 2021, said: “Taking ordinary southern Californian scenes as his subject matter, Gomez offers us glimpses of the human experience amid societal change.”

“The work has gotten continuously darker over the past few years,” said the 42-year-old artist who, dressed in a sweatshirt and drinking coffee, noted that this shift “coincided with becoming a dad.”

“On one hand, some sort of levity is interjected through the iconography that kids are immersed in,” he added, referring to Looney Tunes’ Tasmanian Devil seemingly about to swing through a glass door in one painting, and stuffed cuddly toys lined up along a windowsill in another. “But the overall tone is much more sinister. It’s hard to remain optimistic.”

"Progress maker," from 2023, painted using acrylic on canvas.

The painting “Lights, Camera, Action,” for instance, may reference the glitz and glamour of Hollywood in its title, yet the depiction of a lit-up tent highlights the fact that LA’s unhoused population increased by 9% between 2022 and 2023, according to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA). “You can’t not see it,” said Gomez of the situation. “When I first moved to LA in 2006, (homelessness) was sort of contained in Skid Row; now it’s in every part of the city, really.”

Blurring the line between reality and artifice

Gomez grew up in Chicago and moved to Los Angeles in 2006 to study at the California Institute of the Arts. He found not only his subject matter in his adopted hometown, but also his signature hyper-realist painting style, influenced by local artists such as Ed Rusha and Jack Goldstein, as well the city’s creative industries.

Working with a team of assistants, he compares his production methods to “a very, very small, scaled-down boutique Hollywood movie studio or prop house.” The paintings begin as digital collages that are then recreated on canvas using a physical airbrush — a technique “invented as a way to retouch photos, but which has also been implemented in backdrops for movies, for movie posters and merchandising,” explained Gomez, adding: “There’s something beguiling about its flatness.”

Sayre Gomez admits his work has become darker over recent years. "It's hard to remain optimistic," he said.

They are paintings that blur the line between reality and artifice, often incorporating digital effects (such as pixelated areas) that were created by analog means. “This sort-of reconstructed false reality is very relatable,” said Gomez. “It is real in some ways, but it’s also part of a larger fiction.”

Sculptures also play a role in this dichotomy. “The Promise,” for instance, is a recreation of an electric vehicle charging station, 3D-printed — by fabricators who work with film and television production company Lucasfilm — to look burned and melted.

Meanwhile, “Scale Replica of the Past, Present, and Future (Peabody Werden House)” is based on a Victorian bungalow, built in 1895 in the “working class but now gentrifying” LA suburb of Boyle Heights. Recently saved from demolition by preservationists, the property was pulled by digger to an empty lot across the street in 2016. “And it’s still sitting there, on stilts; I drove by it just the other day,” said Gomez, who hired a Hollywood prop designer to produce the dollhouse-scale piece, which is being shown in Brussels surrounded by paintings of idealized LA sunsets and has since been sold to Museum Voorlinden in the Netherlands.

The Broad Museum in Los Angeles has also recently added Gomez’s work to its collection. The paintings “Diamonds and Pearls” and “The Whole Wide World is a Haunted House” (depicting nail salon signage and an abandoned strip mall, respectively) are included in the museum’s new exhibition “Desire, Knowledge, and Hope (with Smog)” — a group show of LA-based artists titled after a work by the late conceptual American artist John Baldessari.

Gomez's photo-realistic work is currently appearing in a solo show at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels, Belgium (above) and a group show at The Broad in Los Angeles.

“One of the things that Sayre Gomez brings to the exhibition is that he focuses on Los Angeles as it is, rather than a projection of Los Angeles, which is not as easy to do as it sounds,” explained The Broad’s curator Ed Schad. “Even though his work is based on hyper-real moments — whether that’s a burned-up trash can or a construction site — it feels almost surreal. And the city, with our empty buildings and businesses and our great unhoused problem, does present itself as a strange, almost sci-fi reality.”

At the same time, LA’s art scene is thriving —– a point touched upon by Gomez at Xavier Hufkens, where a series of paintings of glass doors (each titled “That Which I Should Have Done I Did Not Do”) includes one looking over once run-down parts of the city now being populated by global galleries including David Zwirner.

But in the midst of this apocalyptic narrative, Gomez admits to something of a love story — he cannot imagine himself living and making work elsewhere.

“I mean, I walk out the door and I’m like, ‘God, this is depressing’,” he said. “But California is also so beautiful. It’s a weird thing.”

Phương Nhung

Phương Nhung